The croissant diet or how I eliminated my spare tire by eating croissants using the six scariest words in the English language: saturated fat, insulin resistance, and free radicals.

The Croissant Diet

While researching for the series “The ROS Theory of Obesity,” I came across Valerie Reeves’s thesis via a post from Hyperlipid. She fed a group of mice a diet with an even split of carbohydrates and fat and relatively low protein. Most of the fat was stearic acid, a long-chain saturated fat that is most common in beef fat, cocoa butter, and dairy fat. The mice fed this diet became very lean, but in particular, they had very little abdominal fat and more lean mass compared to mice fed a high starch diet or mice fed a diet high in oleic acid, a monounsaturated fat found in olive oil.

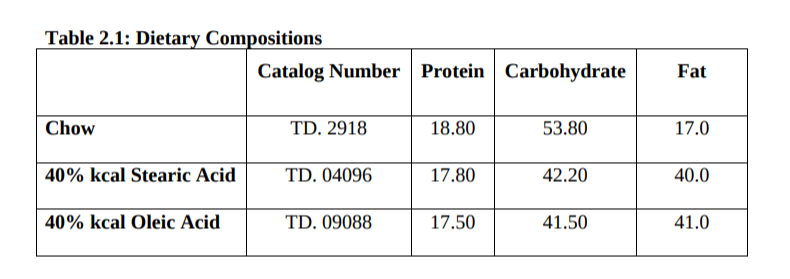

The diet was described like this:

The line labeled “40% kcal stearic acid” shows the macronutrient composition of the diet that produced the lean mice – about 18% protein with 40 percent fat and 42% carbohydrate, with most (85%) of the fat being stearic acid.

I do not know what you see when you look at that table, but I see a croissant recipe.

And so, I thought, “Does this mean I could lose weight by eating croissants?!” And I’m THAT guy, so of course, I did it. And it worked (see my video explanation here).

How I Got Here

I’m a 44-year-old man from upstate New York. I read Weston Price’s “Nutrition and Physical Degeneration” when I was 25, where I learned that white flour, white sugar, and vegetable oil were “the displacing foods of modern commerce.” I did the Atkins diet for the first time sometime around 2002. My longstanding belief is that the highest quality foods are animal-based foods from animals raised on pasture with fresh air and sunshine. These realizations led me to leave my job at the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project and start a career raising pastured pigs. Over the years, I designed diets for the pigs that would minimize the amount of polyunsaturated fat in the pig fat, believing polyunsaturated fat (PUFA) to be the source of many of our metabolic problems. (see Firebrand Meats low PUFA pork here.)

I also have a chef background.

While I was living in New York after college, I was doing cancer research in a molecular biology lab at the Memorial Sloan-Kettering cancer center. I signed up for a 13-week intensive training at what was at the time the French Culinary Institute (now the International Culinary Center). I like good food, I love food history, and I love understanding regional cuisines. I’m a nerd, and I will spend hours perusing historical food consumption trends from the FAO or flipping through my original manuscript of The China Health Study.

Much of the last 20 years I have spent in and out of ketosis, dabbling with intermittent fasting, and attempting to eat as many nutrient-rich animal foods as possible – egg yolks, bone broth, pork skin, liver (I don’t like the taste of liver, much to my personal chagrin). But I’ve also been very busy, and I wouldn’t describe my personality as “disciplined” or “rigorous.” But I am “fun”!

Which is to say that I cheated a lot. Additionally, I drink immoderately, mostly red wine and beer. I’ve struggled with my waistline my entire life as has most everyone in my immediate family.

The last year or two I had been particularly undisciplined.

I stepped on the scale on January 1st of 2019 to the shocking revelation that my BMI had swelled to over 37. Morbid obesity is defined as having a BMI over 40. I am barrel-chested with thick forearms, and so I carry my weight well. I stay active on the farm, and I play full-court basketball weekly. Still, things weren’t looking great.

Like so many Americans, I promised myself that this year would be different. I knew what to do, I would go keto. Numerous times in my life, I have lost over thirty pounds on keto diets in a relatively short period of time. But I wasn’t twenty-five anymore, and the weight didn’t come off like it used to. I spent the first half of 2019 in ketosis two-thirds of the time. I was using intermittent fasting, consuming almost all of my calories between 3 pm and 10 pm. I lost a little weight. But I still had a BMI of 35 and a noticeable “spare tire,” the classic symbol of male, middle-aged abdominal obesity. I was still drinking dry red wine during this period, but I had mostly cut out the beer.

As a younger person, I was always able to lose weight while drinking all of the wine I wanted.

I don’t have tons of pictures from this time period because fat people don’t like to be photographed. But there are always fish pics. On June 28th, I caught a beautiful bass, and my brother snapped the obligatory fish pic. And there, behind the fish, is my spare tire in all of its glory, after six months of keto, intermittent fasting, and red wine.

Why I Thought the Croissant Diet Would Work

Much of this time, I was researching for The ROS Theory Of Obesity. The more I read and researched and thought about The French Diet and the traditional diet of European descended farmers in the Eastern US, the more I came back to one inescapable fact.

A primary regulator of whole-body energy balance is the ratio of saturated to unsaturated fat.

My long-held belief that obesity was caused by carbohydrate consumption was wavering. I had always had some cognitive dissonance about low-carb dieting because, although it clearly works for a lot of people, I also know that French people in 1970 ate something like 1200 calories a day of white flour, white sugar, and potatoes — and remained lean. There is something to low-carb dieting, but it doesn’t tell the whole croissant diet story.

My research had uncovered several facts that were illuminating.

- Mice fed stearic acid, a long-chain saturated fat, lost abdominal fat, whereas mice fed oleic acid, the monounsaturated fat that makes up 70% of olive oil, gained abdominal fat, compared to low-fat controls.

- Mice who lacked the ability to convert saturated fat into monounsaturated fat had lifetime protection against obesity.

- Obese humans make three times as much of the enzyme that converts saturated fat into unsaturated fat and have body fat that is significantly more unsaturated.

This is Part One of a six-part series.

Brad Marshall is the author of the Blog Fire In A Bottle, the author of The SCD1 Theory of Obesity and the creator of The Croissant Diet. Mildly obsessed with food and its history, his work focuses on trying to place current ideas about diet, including keto and carnivore diets into the framework of traditional Dietary patterns. For instance, the French diet before 1970 combined flour, sugar, butter and wine and the population was lean.

Brad Marshall is the author of the Blog Fire In A Bottle, the author of The SCD1 Theory of Obesity and the creator of The Croissant Diet. Mildly obsessed with food and its history, his work focuses on trying to place current ideas about diet, including keto and carnivore diets into the framework of traditional Dietary patterns. For instance, the French diet before 1970 combined flour, sugar, butter and wine and the population was lean.

Brad wrote The ROS Theory of Obesity which posits that ROS generation in the mitochondria of fat cells could provide the mechanism that explains why a traditional chinese peasant diet – low fat with 85% of calories from starch; a French diet combining butter, wine and flour and a modern keto diet could all be expected to produce leanness but combining flour with polyunsaturated fats is a recipe for obesity. The core idea comes from the Protons thread of Peter Dobromylskyj’s blog Hyperlipid. Brad tested this hypothesis with his dietary experiment The Croissant Diet. The SCD1 Theory of Obesity is the second part of the theory. It deals with the composition of stored body fat, which gets blended with dietary fat before being burned in the mitochondria